Once upon a time, there was a small pizzeria in the heart of Apeldoorn. The owner, Antonio, was a master pizza maker. His dough was light and airy, his tomato sauce perfectly seasoned, and his customers came from far and wide for a slice of Italian perfection.

But Antonio had a bigger plan: he wanted to turn his sole proprietorship into a chain. He dreamed of multiple branches, a loyal customer base and a brand known for quality and speed.

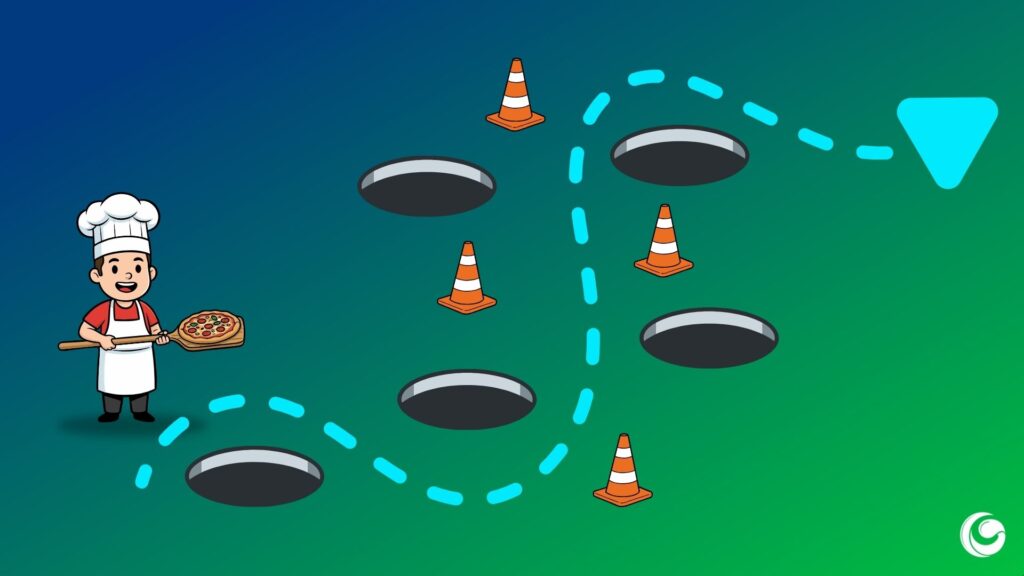

Antonio soon discovered that baking good pizzas was not enough to realise this ambition. His strategy for growth and differentiation could only succeed if his processes functioned properly. But in doing so, he encountered the same pitfalls that many organisations recognise.

Pitfall 1: Process management as an end in itself

Antonio decided that everything had to be recorded in detail. He made an Excel list of all processes: from kneading the dough to delivering the pizzas to the customer. Each employee was asked to describe his or her processes. In a short time, thick documents, process drawings and diagrams were created.

At the end of the year, Antonio looked proudly at what had been achieved. But when he asked his wife, “What have all these processes actually contributed to our strategy? Have we become faster? Are customers more satisfied?” there was silence. The documentation was impressive, but the strategy still felt abstract.

There, Antonio realised something fundamental: process management only works if you start with the mission, vision and strategy. The question is not “Which processes can we describe?” but “Which processes really contribute to what we want to achieve?”

His strategic ambition was now clear: he wanted to grow the pizzeria without compromising on quality. His promise to customers was simple and distinctive: a freshly baked pizza on the table within 20 minutes. Speed was therefore not an operational detail, but a conscious strategic choice.

To put this strategy into practice, Antonio measured his processes against a new yardstick. He linked his strategic goals to the most important processes in an overview. For each process, he asked himself: does this directly contribute to our promise of speed? Does it indirectly support that promise? Or does it have little impact?

It became clear at a glance where the real leverage lay. Processes such as order intake, kitchen preparation and coordination with delivery drivers proved to be crucial, while other processes contributed little to his strategic goal. From that moment on, Antonio focused his attention on the processes that really made a difference, rather than trying to optimise everything at once without clear priorities.

Pitfall 2: Process management as a paper tiger

At another branch of Antonio's growing chain, everything seemed to be in order. The relevant processes had been described, critical performance indicators had been established, and the whole thing looked professional.

But when Antonio himself spent an evening working on the shop floor, he quickly recognised the old pattern. Orders came in to the kitchen via the waiting staff, but were delayed or miscommunicated along the way. If something went wrong, the response was often: “That's not my job.” The process existed, but mainly on paper. In practice, it was difficult to manage.

The problem was not the lack of processes, but the lack of ownership. No one felt responsible for the whole.

Antonio decided to take a different approach. He made process roles explicit and appointed process owners with authority over the entire process: from order to delivery. These were people who were not only allowed to identify issues, but who could also make decisions and take corrective action.

To clarify this, he organised a gun and claim session. In this session, employees explicitly stated what they wanted to give to others and what responsibilities they wanted to claim for themselves, both within the line organisation and within the process. This created clarity and commitment. People dared to take ownership, improvements were implemented more quickly, and there was visible pride in the joint process results.

From that moment on, the process really began to move forward.

Pitfall 3: No culture of continuous improvement

At a branch of Antonio's pizzeria in Arnhem, everything seemed to be organised down to the last detail. Dashboards in the kitchen showed the progress of orders, the team regularly discussed the division of labour, and in this way they tried to maintain quality and speed.

Nevertheless, implementation was difficult. Improvements were slow and ideas from the shop floor often went unheeded. “We've known for a long time where the problems lie,” said one employee, “but we're not allowed to do anything about them ourselves.” Process management did exist, but it was mainly a top-down system. The knowledge of the people who did the work on a daily basis was hardly utilised.

Antonio realised that real progress can only be achieved if employees are able to actively contribute to improvements. He introduced short daily and weekly meetings in which the team discussed bottlenecks, ideas and small actions. Mistakes were discussed openly, successes were shared and small improvements were addressed immediately.

Slowly but surely, process management changed from a static system into a dynamic tool. The team felt a sense of ownership, improvements were implemented more quickly, and the culture of continuous improvement became a visible part of everyday work.

Conclusion

Antonio's story shows that process management should never be an end in itself: it is a means to actually realise strategy. The three pitfalls discussed are the most common obstacles in practice: processes that have not been chosen strategically, a lack of ownership and the absence of a culture of continuous improvement.

By recognising and overcoming these pitfalls, process management can evolve from a static system on paper into a powerful tool that actually makes the strategy work. It means carefully selecting which processes matter, giving people responsibility and authority, and creating an environment in which bottom-up improvement is a matter of course.

It is these elements that help organisations, just like Antonio's pizzeria, to realise their ambitions and get closer to their strategic goals, step by step.