Strategy setting is a popular topic in board rooms and a fertile source for research, education and opinion. Organisations spend a lot of time and money on it, at the same time there is a lot of research showing that execution often goes differently and results are severely disappointing. Strategy Execution is thus trickier than thought. As a Registered Controller and Management Consultant, I want to understand why and, together with IMPROVEN, I contribute to improving the effectiveness of Strategy Execution of organisations. At this place, I share my insights and experiences on this in a series of articles. In the previous article, I characterised Strategy Execution as a balancing act between change and performance. Strategy Execution takes a chosen strategy as its starting point, but how executable is it really and what demands can we make of it? This question is the focus of this second article.

A good strategy convinces stakeholders

Organisations exist not for themselves but to mean something to their stakeholders: customers, funders, employees and the living environment.

The management gives direction, first and foremost by making clear where and for whom the organisation (is). A mission statement is the foundation in which stakeholders should recognise themselves, but does not name concrete achievements and does not have a specific time horizon. A vision translates the mission into certain results for stakeholders and an aspired position of the organisation in its environment in the very long term. The example is Coolblue, known for its slogan: "everything for a smile". Coolblue's mission is to make people happy by selling and delivering consumer electronics. Everything is focused on making not only customers, but also employees smile with that core business. Coolblue is deeply convinced of the value of this experience in people (joy), and turns this into its vision to build leading positions with an obsessive focus on customer satisfaction combined with an omnichannel market approach: via website, app, in-house customer service, physical shops and delivery and installation services.

Mission and vision are primarily intended to link the organisation to stakeholders outside and inside the organisation: do they recognise themselves in the main direction, and do they feel inspired and motivated to commit to the organisation not only morally, but perhaps also materially?

But obtaining concrete commitment from all stakeholders requires more concrete statements about ambitions, the timeframe by which they will be realised and what support is required from stakeholders to achieve them. Including a convincing explanation of how the organisation will achieve these achievements in the environment in which it operates.

The best strategy persuades all stakeholders to commit fully and concretely to the organisation, giving it the time, space, moral support and material and human resources to make it a success. A less convincing strategy produces less commitment and therefore less success.

What convinces employees?

Each stakeholder evaluates a strategy on the attractiveness of its promised performance and the plausibility of the underlying assumptions about the external environment and the organisation's activity choices aligned with it.

Employees, the organisation itself, also assess the strategy for practicality in their own day-to-day work, during strategy execution. For them, the strategy is not only a promise but, above all, a tool, an aid in their daily functioning.

They are perhaps the most critical stakeholders. To get them on board, the strategy itself and the way it is brought to them must align with the way they, as individuals, decide whether or not to commit to it. This can be compared to a consumer's buying decision: the employee gives their "buy-in" to a strategy. By analogy with consumer buying behaviour, the "buy-in" process has four stages, also referred to by the acronym "AIDA". Each stage places a specific requirement on the strategy:

| Stage | Question | A viable strategy is: |

|---|---|---|

| Attention | Am I paying attention to this? | Clear |

| Interest | Is this sufficiently attractive to me? | Attractive and Acceptable |

| Decision | Is it credible? (Then I will basically join in) |

Appropriate and Feasible |

| Action | What exactly is expected of me? (result and activity) |

Concrete |

Attention: a clear story gets more attention

As we become more inundated with information, we develop thicker filters for messages we pay attention to at all, and we are more likely to drop out the more difficult it is to get them through to us. So the same applies to a strategy.

A message must be presented in an attractive way to get attention. The typical pitfall for conveying a strategy is that it is too complex and comprehensive for consumption, and therefore not understood let alone followed.

Clarity, then: easy to interpret. Of course, how employees perceive clarity depends on their backgrounds and preferences, but conciseness and simplicity almost always contribute to it:

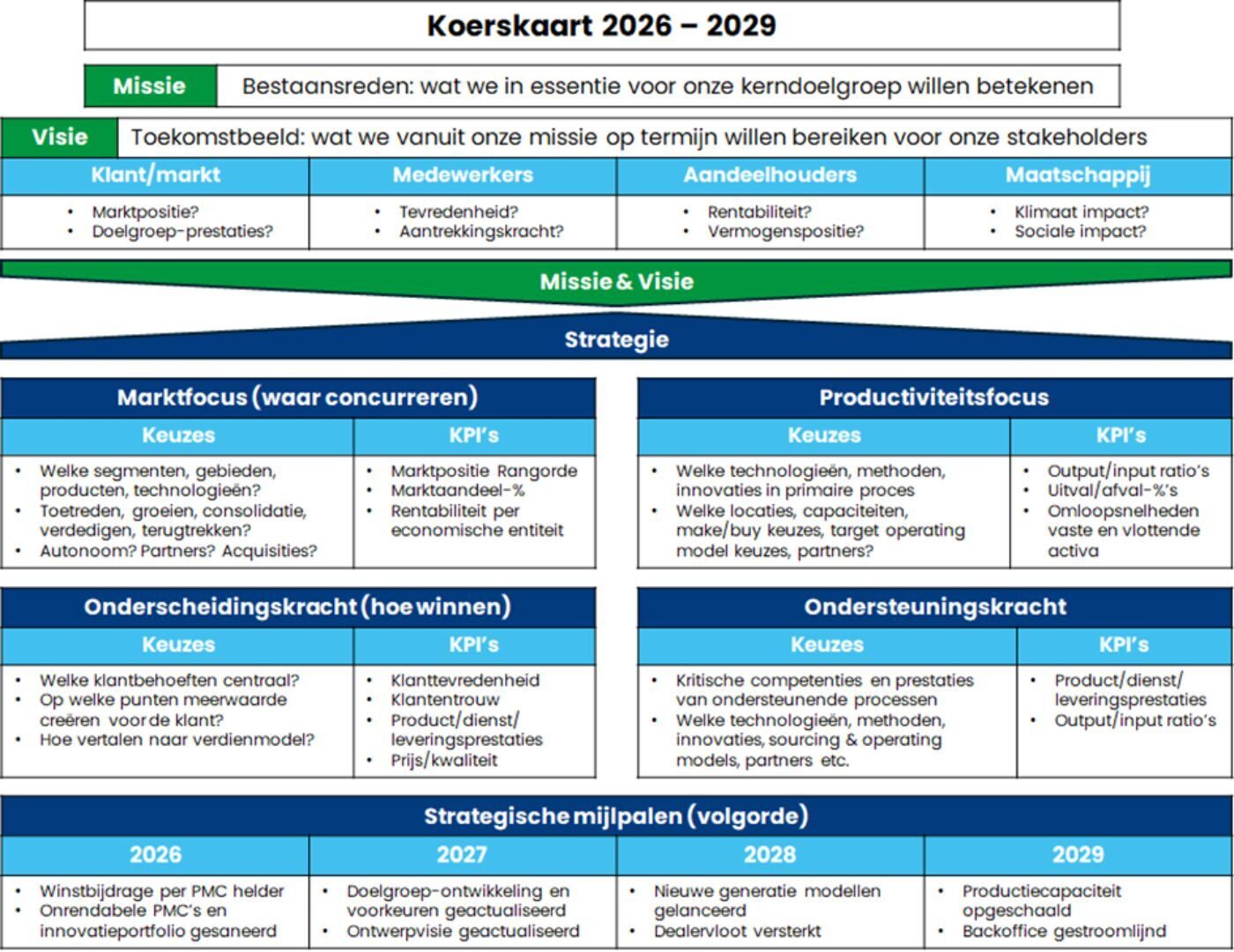

Conciseness ensures that we do not spend unnecessary time and effort consuming the message . We like to see the essence articulated in a concise and engaging way. In our view, a strategy should therefore be able to be summarised on 1-2 A4 in the form of a "Course Map":

- An A4 describes the organisation's direction: what markets/areas the organisation does and does not want to focus on, in what way it wants to distinguish itself in them, and how this is done in a productive way that generates sufficient returns.

- An A4 describes the change programme to pursue that course: projects to strengthen competences, create innovations, take up new positions, establish partnerships, et cetera.

Under the heading "Action", I show an example of a Course Map.

Simplicity ensures that it does not take unnecessary time and effort to understand the message. It requires:

- Good structure: a structure that shows the reader/listener how the new strategy links the organisation's history, current position and future ambition.

- Consistency: a strategy consists of choices in different areas and levels of operations. The reader/listener wants to understand how they are related and is allergic to contradictions.

- Simplicity: woolly and complicated language irritates and quickly raises the question of whether the authors themselves understand it.

Interest: an attractive perspective enthuses

Stakeholders give their support to the organisation as long as they expect to gain something from it. So do the organisation's own employees. There are two sides to this, let's say a positive and a negative one.

The positive side is about the attractiveness of a strategy. About the fit between the organisation's values, goals and strategy with those of employees, and thus their motivation to contribute to it. Their material and personal development is partly determined by the direction of the organisation itself and the opportunities they see for themselves in it. For instance, people in a digital scale-up will feel more attracted to a strategy with fierce growth targets, high rewards and ditto risks than a strategy of consolidation and perpetuation. This is not to say that it is wise to speak organisation's mind, but shaping strategy without understanding the mood and needs of employees is certainly unwise. Even better is to involve employees directly in strategy formulation. Not symbolically, but with actual input based on expertise, insight and vision.

The negative side is about the acceptability of a strategy. About the limits an organisation that sets itself in the goals and strategy itself and in its realisation. In Machiavelli's world, the end justified the means, but in our contemporary world, the opposite is true. Morally and legally, we have standards and rules to adhere to, but also from a risk-awareness perspective, in a world full of uncertainties, it is important to set limits on our actions. These aspects of strategy must also align with employees' values, norms and risk awareness.

It can be tempting to highlight the attractiveness of a strategy anyway, but it is unfair and unrealistic to underestimate its limits. An organisation comes out of a cold shower when the path to the golden mountains turns out to be strewn with pitfalls. Not only does execution fare worse in the absence of preparation for boundaries that do exist, but it also erodes trust among employees in the organisation and its leadership. And it is precisely this trust that forms the foundation of cooperation.

Decision: a credible story gives confidence

A strategy may outline a beckoning perspective with clear boundaries, but if it is based on quicksand, it still doesn't buy you anything as a stakeholder. Employees know the environment, market and organisation better than anyone and can and will judge a strategy on credibility: (a) does the direction fit the situation and (b) is the outlined route feasible?

(a) Does the strategy fit the situation?

From an ivory tower, management can easily get a different picture of the organisation's position and perspective than the people working in it. For a strategy to get people on board, the story must connect past, present and future in a conclusive way, and answer basic questions:

Current position

- How are we performing against stakeholder requirements and expectations? Customers, funders, employees,...

- How are we doing against competitors?

- What makes us do better or worse?

- What are the prospects under unchanged policies?

Desired position

- In which markets and with which activities do we have the best opportunities?

- What can we achieve there for our stakeholders?

Strategy

- Which markets and activities do we choose, and where do we stop?

- What differentiates us in those markets, and how do we ensure that we earn enough from them as an organisation?

- How do we prepare the organisation for this future? (change)

(b) Is the chosen route feasible?

Wishful thinking always lurks in strategy formulation, after all, we want the best for the future. Therefore, alignment with the situation already makes an important contribution to the feasibility of a strategy, because it addresses the right issues. But even then, there remains enough substance to under- or overestimate the impact of environmental developments or one's own capabilities and limitations. And there is enough dynamism and complexity in and around the organisation to overlook developments or misjudge links between measures and effects.

Knowing this, it is important to make clear what the critical success factors are in a strategy, what assumptions have been made, and what the main uncertainties and risks are. No dry enumeration of factors, no doomsday stories either, but realistic beats and an explanation of trade-offs made. Scenarios can be a good tool for making and explaining trade-offs, provided they are kept to a minimum and limited in content to only the most critical factors.

Action: concrete on results and change task

Once the feasibility test is also passed, and people are eager to get to work on it, one question remains: what are we as a team and myself going to contribute to it?

Detailed answers to this question need not be provided by a strategy; that is what plans are for. But a strategy does need to show by means of picket lines where and how the route will roughly run. The picket lines take the form of KPIs, which express what will eventually be achieved and the intermediate results needed to get there for the organisation as a whole and the key work areas below. These KPIs reflect the "run" side of operations.

To get on that "runway", the organisation will have to adapt and improve in vital areas. Such a strategic "change" usually involves several projects, which give the organisation the competences and put it in the position to run the course as mapped out. A strategy is not complete without a clear description of these strategic change projects.

For the organisation itself, it is clear if the strategy process concludes with a concise summary of policy choices and KPIs. I call this the Course Map: literally a map that you can print on A4 or A3 size and hang by your desk or by the coffee machine, in the canteen, factory hall etc. Below is a fictitious example to illustrate:

A course map is by definition very concise and purely intended to make the direction clear. A strategic, tactical and operational plan differentiates this over time and to the organisation, processes and allocation of financial resources.

You create a workable strategy together

In case there is any doubt: without direct employee input, a strategy is unlikely to convince.

This is true just for the substantive quality of the strategy itself. It is also important for employees' sense of commitment and motivation to be known in determining the future direction. This also concerns them personally.

A strategy arrived at through dialogue between management and organisation is therefore more likely to succeed. You create a workable strategy together.

Collaboration is also the key word in Strategy Execution. More on that in the next article, where we look at the backbone of Strategy Execution: processes.